Kelan Luker was different from the other quarterbacks who came through Art Briles’s Stephenville dynasty in the 1990s.

Most grew up dreaming of playing for the Yellowjackets. Luker, however, moved to Stephenville in eighth grade, unaware of the program’s significance. He didn’t even know who Briles was. His junior high coach had to chase him down after practice just to get him to lift weights—Luker preferred sneaking home.

But on the field, he played quarterback with the freedom, creativity, and risk-taking honed in the six-man football he grew up playing while his father coached in Valera, Texas. That gunslinging background was a perfect fit for Briles’s revolutionary spread offense, where the Yellowjackets lined up with five wide receivers and aired it out every two to three plays.

In his 1998 senior season, Luker threw for 4,697 yards and 49 touchdowns—despite often sitting after halftime. Stephenville’s offense set the national single-season yardage record with 8,664 yards. Luker was named Dave Campbell’s Texas Football “Quarterback of the Decade” for the ’90s.

“He’s got the quickest release of any guy I’ve ever been around,” Briles told Sports Illustrated in 2008. “He’s got an amazing arm, and he gets rid of the ball faster than I thought was possible.”

Yet even as he led a football-crazed town to a state championship, Luker felt out of place. His long hair and laid-back demeanor hinted at a musician’s soul he hadn’t yet discovered.

“You’d think he might be a surf instructor out in California,” said Sterling Doty, Luker’s former teammate and now Stephenville’s head coach.

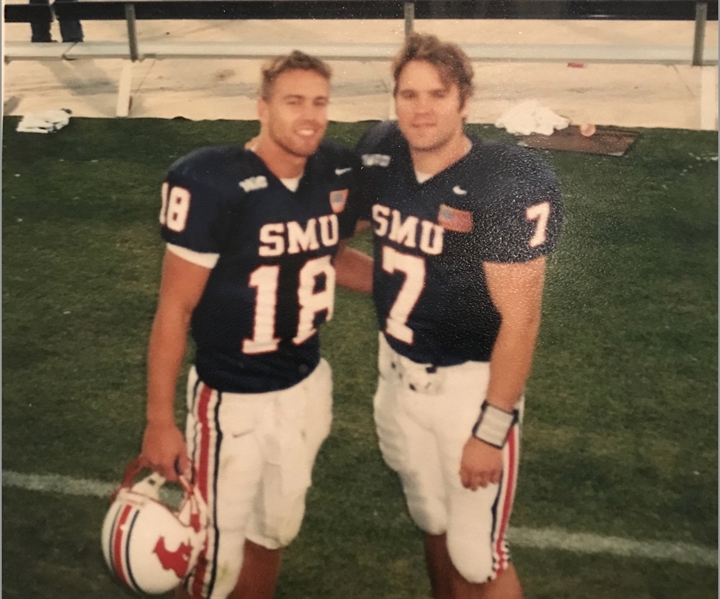

It wasn’t until he left Stephenville for SMU that Luker found an outlet to explore that other side of himself. He met Texarkana guitarist John David Black, whose talent on the strings was mesmerizing. His roommate, fellow Stephenville grad Robert Lilly, bought a guitar and started playing Texas country riffs late into the night.

Luker’s older brother, Seth, wanted to manage a rock band, and Kelan tagged along to shows across Dallas-Fort Worth. He fell in love with a band called Edgewater and realized he was more of a rock guy than his country-loving roommate. He remembered the adrenaline rush of “Mandatory Metallica” days in the Stephenville weight room.

But his football career at SMU stalled. As a freshman, he completed just 39% of his passes in limited action, then redshirted his second year. In 2001, he was benched after three starts. By 2002, he was favored to reclaim the starting job under new head coach Phil Bennett—three other quarterbacks had quit the team.

Bennett, however, refused to let quarterbacks wear red non-contact jerseys in spring practice. He wanted to test Luker’s toughness. Late in camp, Luker took a QB draw up the middle and was hit just wrong. Spinal concussion. A week later, Bennett asked if he was ready to suit up again, dismissing the nerve shocks Luker felt down to his feet.

The injury, combined with three straight losing seasons and constant coaching turnover, made Luker realize he didn’t love football anymore.

“Luckily, music was there,” Luker said. “Because I didn’t know what I was going to do. Football was pretty much my life until that point.”

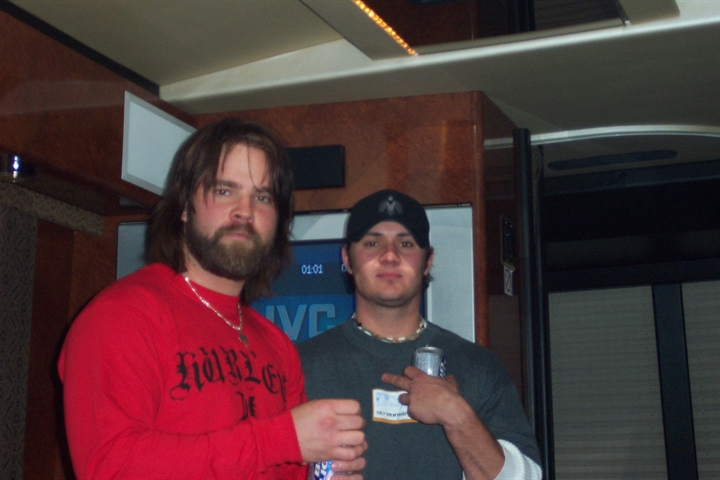

Seth had started a rock band, Submersed, with some Stephenville friends. Though Luker had only learned bass eight months earlier, the band wanted his songwriting skills after he stumbled upon a chord progression late one night in his SMU apartment. His bass playing, they assured him, would catch up.

“Some people want to get good so everyone notices how good they are,” Luker said. “Me, I just wanted to write songs.”

They caught the right eyes. Mark Tremonti, guitarist for the mega-popular band Creed, saw them at a record showcase in 2002 and moved them into a house next to his in Orlando for the summer. Meanwhile, Bennett kept calling Luker, asking if he was coming to summer workouts. Luker would take the calls while his bandmates played pinball as Tremonti shredded on his guitar.

He told Bennett he was done. That same July day, Submersed signed with Creed’s label, Wind-Up Records.

But rock stardom came with an expiration date. Creed’s formula—hook-heavy radio anthems like Higher and With Arms Wide Open—had peaked by the time Submersed released In Due Time in 2004. Their debut was caught in the genre’s downfall.

Then, in 2005, Seth was diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer. Without their leader, the band drifted apart. Luker and his friend TJ moved from Orlando to Ocala, living with another buddy from Stephenville. One day, Luker walked in on a living room church service. His friend told him he had to meet the preacher’s daughter.

He and Kim started dating and attending church, throwing him into another identity crisis. His bandmates partied, but he wanted to read his Bible at night. He was living a double life—out of place, just as he’d felt in Stephenville.

By 2007, as the band wrapped its second album, Immortal Verses, Luker spent more time tossing a football around before shows. His bandmates took notice.

“You should go play football,” they’d joke.

For a long time, he resisted. “I already did.”

“It was always hard for me to separate myself from football,” Luker said. “I didn’t sit down to watch a football game for three to four years.”

But football wasn’t done with him.

With Submersed’s breakup looming, Luker confided in Seth: he wanted to return to college football. Tarleton State head coach Sam McElroy had a backup spot.

So in 2008, Luker returned to Stephenville—not as a star quarterback, but as a 27-year-old Division II backup. The strength coach occasionally blasted a Submersed song during workouts. His teammates called him “the old man.”

Luker didn’t care. He wasn’t there for glory but to prepare for coaching.

After graduating, he and Kim moved to Florida. Then, in 2014, his former teammate Sterling Doty hired him as Magnolia High School’s co-offensive coordinator.

Doty had described Luker the player as a duck on the pond - on the surface, calm, almost serene. But on the bottom, legs flapping, working to stay afloat. It’s a fitting analogy for Luker the man, too. In both his lives, as a quarterback and rockstar, he came across as “Cool Hand Luke” to the outside world. In his own world, however, still searching for himself.

“He sees the other side of the coin and knows that there are things kids go through that maybe we don’t see,” Doty said.

That coaching quality was especially important when Doty and Luker returned to their alma mater, Stephenville, for the 2019 season. Luker himself never felt pressure when he was the quarterback. He had the best coach and so many good athletes around him that he couldn’t help but be confident.

Almost two decades later, however, he saw the weight of expectations on his quarterbacks, carrying the burden of a state title “drought” since 2012. That’s why winning the 2021 Class 4A Division I State Championship as a coach felt so much different than when he did it as a player. Back then he was excited for himself. Now he was excited for them, happy they didn’t have to deal with the pressure his athletic achievements had helped place on them anymore.

Kelan Luker lives in a nice little house next to Gustine High School, one of the smallest public schools in Texas with an enrollment of 38. He’s the head basketball coach and an assistant football coach. But in a town this tiny he also doubles as the elementary school P.E. teacher. It’s turned into his favorite role.

“Being around those little kids that don’t know anything from anything, just happy, running around giving you hugs and high fives, that kind of stuff builds me up every day,” Luker said.

The kids are too innocent to know how much they’re helping him. After his recent divorce, which came just after Stephenville’s 2021 title, Luker’s ex-wife and five-year-old daughter moved back to Florida while he moved near his parents. His father is a former coach and principal in Gustine, and his uncle is on the school board. It was an opportunity to get back into coaching, but mostly to work his life out in the middle of nowhere where it’s quiet enough to hear God tell him what to do next.

When Dave Campbell’s Texas Football reached out pitching a “Where is he now?” story on the former Stephenville star named Quarterback of the Decade for the 90s, Luker’s first thought was, “Man, I don’t know.” Right now he’s in rebuild mode, reading his Bible under a night sky with every star visible because there’s not enough human light to interfere. But even out here, the more people he meets the more people he realizes have gone through divorces.

This is just a chapter in a book that’s included a high school state championship, a six-year rock band venture, a return to football as a 27-year-old college quarterback and another state championship as a coach at his alma mater. You don’t finish the book by reading the pleasant chapters and skipping the rest.

All athletes want to be rock stars and all rock stars want to be athletes, but no one’s done it like Kelan Luker.

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.